Silas Burdoo (1748 – 1837)

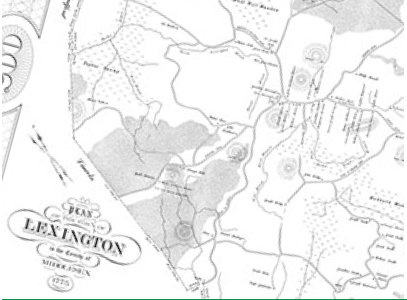

Silas Burdoo was a third-generation free Black Lexingtonian. His grandmother Ann Soloman Burdoo was admitted to the Parish in Lexington in 1708. His father Phillip Jr. was baptized at the Parish in Lexington in 1709.

Silas Burdoo fought on the Lexington Green on April 19, 1775. After the Battle of Lexington and Concord, he served with the 9th Massachusetts Regiment during the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775; his unit was at the nearby Charlestown Common.

In 1781, Silas Burdoo was one of three Lexingtonians, along with William Diamond, to serve garrison duty at Gallows Hill, on the bank of the Hudson River south of West Point, New York.

Note: No known picture of Silas Burdoo was available for this portrait. Louis Colon, Lexington resident, served as the model for the banner portrait.

Eli George Biddle (1846 – 1940)

Eli George Biddle was sixteen years old when he met a recruiter in Boston, Massachusetts and enlisted to serve in the Civil War. Private Biddle was seriously wounded in the neck and shoulder during the assault on Battery Wagner on July 18th, 1863; he was awarded a Purple Heart. As a veteran, Reverend Eli George Biddle served as the state chaplain of the Grand Army of the Republic in Massachusetts. When he died in 1940 at the age of 94, he was the last surviving member of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment.

George H. Coblyn, his grandson, was a long time Lexington resident who earned two Purple Hearts and three Bronze Stars from World War II and Korea and retired as a major from the United States Army.

Edward Brooke III (1919 – 2015)

In 1966, Edward W. Brooke III became the first Black citizen elected to the United States Senate by popular vote. The previous Black citizens to serve as senators, Blanche K. Bruce and Hiram R. Revels, both Republicans, were elected not by voters but by the Mississippi Legislature in the 1870s.

Mr. Brooke won his Senate seat by nearly a half-million votes in 1966 and was re-elected in 1972. He was the first Republican senator to demand Nixon’s resignation.

Prior to becoming a senator, Mr. Brooke was twice elected attorney general of Massachusetts, making him the first Black citizen to be elected attorney general of any state.

Adelaide McGuinn Cromwell was his cousin.

Shirley Chisholm (1924 – 2005)

Shirley Anita St. Hill Chisholm became the first Black woman elected to Congress when she won New York’s 12th District in 1968. In 1972, Ms. Chisholm was the first woman and Black citizen to seek the nomination for president of the United States from one of the two major political parties. Ms. Chisholm sought to amass “enough delegates to have clout” as a powerbroker at the convention in July 1972. She planned to demand concessions from the winning Democratic candidate: naming a Black vice-presidential candidate to the ticket and securing diverse Cabinet and agency appointments, including a woman to lead the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) and a Native American as Secretary of the Interior.

Prior to becoming a member of Congress, Ms. Chisholm ran for and became the second African American in the New York State Legislature in 1964. In 1977, she became the first Black woman and second woman ever to serve on the powerful House Rules Committee which sets the terms of debate for every bill that reaches the House Floor.

Adelaide McGuinn Cromwell (1919 – 2019)

In 1969, Adelaide McGuinn Cromwell founded Boston University’s African American Studies program, the country’s second such program and the first to offer a graduate degree in the subject. Prior to joining the Boston University faculty in 1951, Ms. Cromwell was the first Black faculty member of Hunter College in New York City and of Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts.

In 1940, Ms. Cromwell earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in Sociology from Smith College; her “mothering aunt,” Otelia Cromwell, was the first African American graduate of Smith College. A year later, Ms. Cromwell earned a Master of Arts in Sociology from the University of Pennsylvania. In 1946, she earned a certificate in social casework from Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania and a Ph.D. in Sociology from Harvard’s Radcliffe College.

Paul Cuffe (1759 – 1817)

In 1812 Paul Cuffe became the first free Black citizen to visit the White House and have an audience with a sitting president. The son of an African father and Wampanoag mother, he built and owned six vessels. In addition to being a wealthy sea captain and entrepreneur, Mr. Cuffe built a school on his property in Westport, Massachusetts that welcomed Black students as well and Native American and White students.

In 1780, Mr. Cuffe and several other free Black citizens petitioned the Massachusetts General Court, requesting that they be exempted from taxation because even though they were landowners they were denied the right to vote. The petition was denied but was subsequently incorporated into the Commonwealth’s new constitution making “all free persons of color liable to taxation, according to the ratio established for white men and granting them the privileges belonging to the other citizens.”

Alan Dawson (1929 – 1996)

Alan Dawson was a legendary drummer and educator, known for his work with the top artists in jazz as well as for his 18-year association with Berklee College of Music in Boston, Massachusetts.

Born in Marietta, Pennsylvania, George “Alan” Dawson was raised in the Roxbury neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts. A longtime resident of Lexington, Mr. Dawson was a cofounder of the Concerned Black Citizens of Lexington in the early 1970s.

While stationed at Fort Dix, Mr. Dawson played with the Army Dance Band from 1951 to 1953. Following his discharge from the Army, he toured Europe with Lionel Hampton. Over several decades, Mr. Dawson played with many jazz legends including Dave Brubeck, Lionel Hampton, and Quincy Jones.

Mr. Dawson’s teaching was inspirational. One of Mr. Dawson’s first students was a young Boston drummer named Tony Williams. According to Mr. Williams, “Mr. Dawson didn't only teach me to play the drums, he taught me how to conduct myself as a musician and as a man.” Osami Mizuno, a jazz drummer and educator from Japan, created and named a drum school and record label in honor of his drum instructor Alan Dawson. And retired Berklee professor John Ramsay, cowrote The Drummer's Complete Vocabulary as Taught by Alan Dawson with his former drum instructor.

Frederick Douglass (c. 1818 – 1895)

Activist, author, and speaker, Frederick Douglass was arguably one of the most prominent leaders of the Abolitionist Movement and a major supporter of equal rights for women.

After self-emancipating, Mr. Douglass married Anna Murray in New York in 1838. That same year, the couple left New York for New Bedford, Massachusetts which was well known for having a thriving free Black community.

Mr. Douglass was the most photographed American of the 1800s. In 1845, he published his autobiography Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave: Written by Himself. in 1847, Mr. Douglass began his first newspaper, The North Star which later became Frederick Douglass’ Paper.

Working with Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Mr. Douglass co-authored an indictment against the organizers of the 1892 Columbian Exposition held in Chicago in an essay titled “Why the Colored American Is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition.”

Mr. Douglass was a powerful and popular orator. On July 5, 1852, he was invited to address the citizens of his hometown, Rochester, New York. This speech is known as “What, To the Slave, Is The Fourth Of July”. On April 14, 1876, Mr. Douglass delivered “Oration in Memory of Abraham Lincoln” at the Unveiling of The Freedmen’s Monument in Lincoln Park, Washington, D.C. And on April 16, 1888, he delivered "I Denounce the So-Called Emancipation as a Stupendous Fraud" on the occasion of the Twenty-Sixth Anniversary of Emancipation in the District of Columbia, Washington, D.C. These three speeches remind us that the primary theme of his work was equality for all Black residents of the United States of America.

Bernard W. Harleston (1930 – )

Former Lexington resident, Bernard Harleston was the first graduate student of color at the University of Rochester, the first African-American tenure-track faculty member hired at Tufts University, and the first African-American president of the City College of New York.

In 2016, Tufts honored this pioneer in higher education and its former dean of the faculty of Arts and Sciences by renaming the South Hall dormitory on the Medford/Somerville campus Harleston Hall.

An alumnus of Howard University in Washington, D.C, Mr. Harleston was also a senior associate at the New England Resource Center for Higher Education at the University of Massachusetts-Boston.

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (1825 – 1911)

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper was a popular poet, author, and lecturer during the nineteenth century. She was the first African American woman to publish a short story and was an influential abolitionist, suffragist, and reformer who cofounded the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs.

Ms. Harper was born to free African American parents in Baltimore, Maryland. Orphaned at the age of three, she was raised by her aunt and uncle, Henrietta and William Watkins. Ms. Harper attended the Watkins Academy for Negro Youth until she was thirteen years old. At twenty-one, Ms. Harper wrote her first small volume of poetry called Forest Leaves.

In 1859, Ms. Harper published a short story in the Anglo-African Magazine called “The Two Offers.” This short story about women’s education was the first short story published by an African American woman.

In 1866, Ms. Harper spoke at the National Woman’s Rights Convention in New York. Her speech entitled, “We Are All Bound Up Together,” urged her fellow attendees to include African American women in their fight for suffrage.

Mae C. Jemison, MD (1956 – ) *

The first Black woman and non-White woman in the world to travel in space, Mae Jemison continues to dedicate her life to science, knowledge, and the arts. Prior to becoming an astronaut, Ms. Jemison entered Stanford University at age 16 on a scholarship. She double-majored in African and Afro-American Studies and in Chemical Engineering. Upon graduation, she enrolled at Cornell University’s Medical School and during this time she also studied in Cambodia, Cuba, and worked for the Flying Doctors in East Africa.

Fluent in Russian, Japanese and Swahili, Dr. Jemison joined the Peace Corps in 1983 and served as a medical officer for two years in Africa. After working with the Peace Corps, Jemison opened a private practice as a doctor.

Dr. Jemison grew up watching the Apollo missions on TV. She was inspired by African American actress Nichelle Nichols who played Lieutenant Uhura on the Star Trek television show and Sally Ride, who became the first American woman in space, to become an astronaut. Her 1992 trip on the space shuttle Endeavor, marked the realization of a childhood dream.

In 1994, Dr. Jemison created an international space camp for students 12-16 years old called The Earth We Share (TEWS). And in 2001, she wrote her first book Find Where the Wind Goes, which was a children’s book about her life.

* Displayed in The Lexington Depot, 13 Depot Square

Sylvia Ferrell-Jones (1957 – 2017)

Sylvia Ferrell-Jones left her mark on Boston as one of the city’s highest-profile leaders of a nonprofit organization. In addition to serving as the President and CEO of YW Boston, she lived in Lexington for two decades and was an active member of Pilgrim Congregational Church.

Ms. Ferrell-Jones earned her bachelor’s degree from Cornell University and her juris doctor from Yale Law School.

In 2015, Ferrell-Jones was awarded the Race Amity Medal of Honor by the National Center for Race Amity. The award honors individuals who have catalyzed progress towards racial justice and creating equity for all. Under Ms. Ferrell-Jones’ leadership, YW Boston offered several programs to advance racial justice and gender equity in the Boston area. Such programs included: Dialogues on Race and Ethnicity, LeadBoston, Youth/Police Dialogues, and the annual Stand Against Racism event.

To honor her extraordinary contributions and continue to build upon her work, YW Boston set up a fund in her name. The Sylvia Ferrell-Jones Fund honors her legacy, passion, and commitment to YW Boston’s mission. The funds directly support YW Boston’s work to eliminate racism and empower women, and promotes peace, justice, freedom, and dignity for all.

Martin Luther King, Jr. (1929 – 1968)

Martin Luther King, Jr., was born Michael Luther King, Jr. in Atlanta, Georgia. Dr. King was a world renown civil rights leader and recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964.

Dr. King attended segregated public schools in Georgia, skipped both the ninth and eleventh grades, and graduated high school at the age of fifteen. He went on to earn a Bachelor of Arts in sociology in 1948 from Morehouse College, in Atlanta, from which both his father and grandfather had graduated. In 1951, Dr. King earned his Bachelor of Divinity from Crozer Theological Seminary in Upland, Pennsylvania. In 1955, he received his PhD in systematic theology from Boston University.

Between 1957 and 1968, Dr. King traveled over six million miles and spoke over twenty-five hundred times. On February 11, 1963, Dr. King spoke to a crowd of 1200 at Lexington High School, Lexington, Massachusetts. During his address, Dr. King said, “The twin evils of housing and employment discrimination...stand as the greatest barriers we face, and if we could get rid of these two I’m sure that there would be progress in other areas.”

Leona W. Martin (1936 – )

For forty-six plus years, Leona W. Martin has been a citizen volunteer and community relations worker in the Town of Lexington. Ms. Martin helped launch the Cary Memorial Library Foundation, once of the town’s most cherished institutions. She was the first Black women elected as a Town Meeting Member. As an elected member of the Lexington Housing Authority, Ms. Martin was the first Black citizen elected to a town wide position.

Ms. Martin was a cofounder of LexFest! and from 1995 to 2005, she served and the Planning Committee Coordinator. LexFest! Connecting Our Cultures was an annual event that was held in and around the Town Center. LexFest! included dance troupes, food stands, activities, and events highlighting the different racial, ethnic and cultural backgrounds of town residents.

Ms. Martin was a founding Board Member of the Association of Black Citizens of Lexington.

Deval Patrick (1956 – )

Deval Patrick is a politician, civil rights lawyer, athor, and businessman. In 2006, Mr. Patrick was elected the first Black governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. He was sworn in as governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts on January 4, 2007 and was sworn in for a second term on January 6, 2011.

Mr. Patrick is the second Black governor elected in the United States. In 1989, Lawrence Douglas Wilder became the first African American in the United States to be elected governor of a state when he won the general election in Virginia.

Born in Chicago, Illinois, Mr. Patrick graduated from Harvard College, Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1978 and earned his law degree from Harvard Law School. After earning his law degree, Mr. Patrick served as a law clerk to a federal appellate judge before joining the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund as a staff attorney.

In 1994, President Clinton appointed Mr. Patrick Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights, the nation’s top civil rights post. In 1997, Mr. Patrick was appointed the first chairperson of Texaco’s Equality and Fairness Task Force where he led a company-wide effort to create a more equitable workplace environment.

As a candidate and incumbent, Governor Patrick visited Lexington, Massachusetts several times. In October 2010, Governor Patrick joined then state Rep. Jay Kaufman for “A Conversation with the Governor” at Cary Hall in Lexington.

Hattie T. Scott Peterson (1913 – 1993) *

Hattie T. Scott Peterson was the first African American female civil engineer in the United States.

Ms. Peterson graduated from Howard University in Washington DC with a Bachelor of Science in Civil Engineering in 1946. She began working as a survey and cartographic engineer for the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in Sacramento, California in 1947. When Ms. Peterson joined the local U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) in 1954, she was the first woman engineer.

Annually the Sacramento district of the USACE grants a Hattie Peterson Inspirational Award in her honor: "The purpose of the Hattie Peterson Award is to recognize the Sacramento District individual whose actions best exemplify the highest qualities of personal and professional perseverance through social challenges."

* Displayed in The Lexington Depot, 13 Depot Square

Florence Price (1887 – 1953)

Florence Beatrice (Smith) Price was the first female composer of African descent to have a symphonic work performed by a major national symphony orchestra. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra played the world premiere of her Symphony No. 1 in E minor on June 15, 1933. Ms. Price’s symphony had come to the attention of Music Director Frederick Stock when it won first prize in the prestigious Wanamaker Competition in 1932.

Born in Little Rock, Arkansas, Ms. Price played in her first piano recital at the age of four and her first composition was published at the age of eleven.

Ms. Price graduated as high school valedictorian at age 14 and left Little Rock in 1904 to attend the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, Massachusetts. She earned a Bachelor of Music degree in 1906, the only one of 2,000 students to pursue a double major (organ and piano performance).

* Displayed in The Lexington Depot, 13 Depot Square

Charlotte E. Ray (1850 – 1911) *

Charlotte E. Ray was the first African American woman to practice law in the United States. Upon graduation from Howard University’s Law School in 1872, Ms. Ray became the first black woman to graduate from an American law school and receive a law degree. At the time, she was the third woman of any race to complete law school.

Ms. Ray graduated from the Institution for the Education of Colored Youth in 1869. This was the only school in the Washington, D.C. area that allowed African American girls to become pupils.

Ms. Ray’s sister Florence Ray also became an attorney. Another sister, poet Henrietta Cordelia Ray, wrote the 80-line ode "Lincoln", which was read at the unveiling of the Emancipation Memorial in Washington, DC, in April 1876. Their father, Charles Bennett Ray, was a journalist, clergyman, and abolitionist who was born in Falmouth, Massachusetts in 1807.

Note: No known picture of Charlotte E. Ray was available for this portrait. The pictures found online are of other notable Black women. Robin Walker, Lexington resident, served as the model for the banner portrait.

* Displayed in The Lexington Depot, 13 Depot Square

William Ridgley, Sr. (1936 – )

William Ridgley, Sr. was one of the first African-American fire department captains in the City of Cambridge, Massachusetts. A long-time Lexington resident, Mr. Ridgley was elected the first Black Lexington Town Meeting member. In the early 1970s, he became the first president of Concerned Black Citizens of Lexington.

Born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Mr. Ridgley enlisted in the United States Army in January 1958. He joined the Cambridge Fire Department in 1961. In 1968, Mr. Ridgley and his family bought a house in Lexington, Massachusetts.

In 1977, Mr. Ridgley was a finalist for the position of Fire Chief for the Lexington Fire Department.

Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin (1842 – 1924)

Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin was an abolitionist and women’s rights activist. Ms. Ruffin was born in Boston to an English-born White mother and a Black father from the island of Martinique. Ms. Ruffin attended integrated schools in Salem, Massachusetts. During the Civil War, Ms. Ruffin recruited African American men for the 54th and 55th Massachusetts infantry regiments. In the 1890s, she was the editor and cofounder of The Women’s Era, the first newspaper published by and for African American women.

In 1893, she cofounded the Woman’s Era Club with her daughter Florida Ridely and Boston school principal Maria Baldwin. The club had two purposes: to offer its members opportunities for self-improvement and to address issues that directly affected the African American community.

In 1895, she cofounded the National Federation of Afro-Am Women, which a year later united with the Colored Women’s League to become the National Association of Colored Women.

She became one of the founding members of the Boston NAACP in 1910.

David Walker (c. 1796 – 1830)

David Walker was a revolutionary writer, abolitionist, and community leader. In 1829, Mr. Walker wrote David Walker’s Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World. The Appeal called for the immediate abolition of slavery and equal rights for Black people. The publication influenced the abolitionist movement and echoes of the Appeal can be heard in Frederick Douglass’s famous 1852 speech, “The Meaning of the Fourth of July for the Negro.”

According to W.E.B. Du Bois, the Appeal was “that tremendous indictment of slavery” that represented the first “program of organized opposition to the action and attitude of the dominant white group (and included) ceaseless agitation and insistent demand for equality.”

Mr. Walker was born a freeman in Wilmington, a small port in the Cape Fear region of North Carolina. His mother was a free Black woman, and his father was an enslaved Black man. As a young man, Mr. Walker lived in Charleston, South Carolina and was a member of an African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church. Fellow church member, Denmark Vesey, launched a slave rebellion in Charleston in 1822.

By 1825, Mr. Walker was living in Boston, Massachusetts and had a store in the North End. He was a member of the Prince Hall Freemasonry and the Massachusetts General Colored Association. Mr. Walker was also a writer and Boston subscription agent for the New York-based Freedom’s Journal. The Journal was the first African-American owned and operated newspaper.

His son Edwin Garrison Walker became the third African American admitted to the Massachusetts Bar and the second African American elected to a state legislature in the United States.

Quock Walker (1753 – c.1810)

Quock Walker was the key plaintiff in a series of cases in the early 1780s that led to his freedom and the abolition of slavery in the Commonwealth.

Mr. Walker was born in Massachusetts. At the age of nine months, he and his parents, known as Mingo and Dinah, were purchased by James Caldwell, a resident of what is now known as the Town of Barre. Mr. Caldwell promised Mr. Walker that he would be emancipated when he turned 25. Isabel Caldwell, then a widow, promised Mr. Walker that he would be emancipated when he turned 21. Nathaniel Jennison, then Ms. Caldwell’s widower, refused to keep the promises of the Caldwells.

In April 1781, Quock Walker, then 28 years old, self-emancipated. His former enslaver, Nathaniel Jennison, severely beat Mr. Walker. Mr. Walker filed a civil suit against Mr. Jennison for assault and battery. A jury awarded Mr. Walker his freedom and £50 in damages.

Mr. Walker won his case before a jury of the Worcester County Court of Common Pleas on June 12, 1781. Elizabeth Freeman aka Mumbet, a Black woman enslaved by John Ashley of Sheffield, Massachusetts, won her case in the Berkshire County Court of Common Pleas in August 1781.

Commonwealth v. Jennison was heard before the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court in April 1783. The lawyers for Mr. Jennison argued that slavery had long been legal in Massachusetts and no statute outlawed it. State Attorney General Robert Treat Paine argued that Mr. Walker was a freeman, making the attack upon him unlawful. The issue of natural rights was raised by Chief Justice William Cushing, who in his charge to the jury stated, “I think the idea of slavery is inconsistent with our conduct and Constitution; and there can be no such thing as the perpetual servitude of a rational creature”.

On July 8, 1783, the jury again found Mr. Walker to be a freeman and found Mr. Jennison guilty of assault. The rulings in the case established the basis for ending slavery in Massachusetts.

Quock Walker and his younger brother Prince married and became landowners in Barre, Massachusetts. Their sister Minor Walker also married and was matriarch of a prominent middle-class black family that valued education, activism, and political involvement. Her son Kwaku Walker Lewis was a conductor on the Underground Railroad.

Ida B. Wells (1862 – 1931)

Ida B. Wells was a civil rights advocate, journalist, and women’s suffragist. She was the co-owner of two newspapers: The Memphis Free Speech and Headlight and Memphis Free Speech. She wrote antilynching editorials for those papers and for papers across the country.

Born in Holly Springs, Mississippi, Ms. Wells was the first child of James Wells, an apprentice carpenter, and Elizabeth Warrenton, a cook. Ms. Well’s family and over 450,000 enslaved Black residents of Mississippi were emancipated when Confederate Mississippi surrendered in 1865.

Ms. Wells was a teacher in rural Mississippi and Memphis, Tennessee. Ms. Wells attend Rust College in her hometown and Fiske University in Nashville, Tennessee. Her father served on the board of trustees of the newly organized Rust College (then called Shaw University).

In 1906 she joined with William E. B. Dubois to promote the Niagara Movement, a group which advocated full civil rights for Black citizens. In 1909, Ms. Wells helped form the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

In 2020, Ida B. Wells was awarded a Pulitzer Prize "for her outstanding and courageous reporting on the horrific and vicious violence against African Americans during the era of lynching."

Granville Tailer Woods (1856 – 1910) *

Granville Tailer Woods was a prolific inventor who earned more than 60 patents in his lifetime. In 1889, he filed his first patent for an improved steam boiler furnace. His later patents were mainly for electrical devices. As an admired and well-respected inventor, he is known as the “Black Thomas Edison.”

Born in Columbus, Ohio, the son of Tailer and Martha Woods. Mr. Woods and his parents were free by virtue of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. The ordinance provided for civil liberties and public education within the new territories but did not allow slavery in the territory that included what would become the state of Ohio.

Mr. Woods invented the first electric railway that was powered with electric lines from above the train. This invention aided in the development of overhead railroad systems in cities such as Chicago, St. Louis, and New York and made travel safer for pedestrians, previously the electric lines had run along the tracks.

He also created induction telegraphy for railroads, the first telegraph service that allowed messages to be sent from moving trains. Thomas Edison lost his patent challenge for this invention. Mr. Woods explained the invention to a reporter for the Cincinnati Commercial Gazette on 10 October 1886:

“By its means, a train dispatcher can tell at once the location of every train on his roads and engineers can learn exactly where all other trains are, thereby greatly reducing the liability to collisions. Each train will be called by its number just as easily as I am talking to you now. Commercial messages may also be sent. A man need not get off the train to send a message, and between Cincinnati and New York he can hear, if he wishes, from his friends every hour.”

Mr. Woods also invented the automatic air brake and Coney Island electric roller coaster.

* Displayed in The Lexington Depot, 13 Depot Square

Artist Statement

Kamali Thornell was commissioned to draw the portraits and create the banners. He studied art at UMass, Amherst and Northeastern University. Mr. Thornell grew up in Dorchester and spent time during his childhood, in Lexington visiting his great aunt, Ruth Perry Curtis, who was an active member of the Church of Our Redeemer and the Lexington League of Women Voters. Her husband, William Childs Curtis, Sr., PhD, passed when Mr. Thornell was young. Mr. Curtis was a Black electrical engineer, who worked for RCA, and led the team that designed the guidance system for NASA’s lunar module, for the first moon landing.